I just saw Ben E King tonight, at the Jazz Cafe in Camden (the above image is a publicity photo from their website, as I wasn't one of those with a mobile phone camera held aloft). It was essentially celebratory: no point in critical comment. When Stand By Me started - whoosh! everyone was there, loudly singing along. And, still with the same backing, the song gave way to several others, including Sam Cooke's Cupid, and ending with a snatch of You Are My Sunshine, which was delightful.

I did have some qualms about his choosing some obvious feelgood soul numbers dulled by familiarity - Mustang Sally, etc - as though this was a tribute band, not the real deal - and I was aware of an element of schtick, as though he was playing Vegas or wherever. But it was heartfelt schtick, if I can put it that way, and economic schtick.

But then again, why the hell shouldn't he sing these songs? He has more right than most. And familiarity was the name of the game, all the biggest Drifters hits (including some he hadn't originally sung on) and solo hits. Interesting that it was the Average White Band stuff which got bigger roars than the earlier hits - though that may have been because they seemed more naturally suited to the band.

I was doorstepped before and after for a vox pop, so made sure I namechecked this blog - and to make it easier for anyone who has googled the name and arrived here, I will repost an earlier entry, below, about the tangled origins of Stand By Me.

What was good to hear was that he seemed in better voice than when I last saw him in 2001, at the Leiber and Stoller Tribute concert at Hammersmith Apollo. You were aware of the limitations of his voice, of course - c'mon, how long has it been since he recorded Spanish Harlem? - but he was working with what he had, and adding a pleasing jazzy counterpoint to the music at times. The band was pretty good, with a trumpet and a sax, and all fairly young - not the disenchanted bunch I saw backing the Johnny Moore Drifters with Benny in the early eighties in Glasgow. But they wanted to get funky - you could tell - so the Drifters stuff didn't always sit well.

People weren't listening in hushed silence, which annoyed me at times - I remonstrated with the person behind me who seemed intent on providing a commentary (hey, at least I keep it for outside or the deep obscurity of this blog). And the amplification wasn't the subtlest I've heard, though that may have helped mask vocal blemishes. But as far as I remember from the last gig I saw there - the late Edwin Starr, and that's going back yonks - it was the same then. Oh, I'm getting old and intolerant. Older. Intoleranter.

So what am I saying here, exactly? I'm glad I went. And when I first caught sight of him waiting at the top of the stairs for the band to finish their introductory numbers it was a moving moment. I saw him last time on the verge of a major change in my life. And given his age (not to mention mine) who knows how many more UK dates he will play? I can tell myself that this is some kind of bookend, that some further change awaits (yeah, age and the only end of age. Big surprise).

But (putting such thoughts aside) you can't - or I can't - get away from the records. Those beautifully crafted productions with his voice in the middle, Leiber or Stoller (or whoever) pointing at him, and his having to let loose his voice and hope for the best - that is what will live. The gigs are a way of our collectively affirming their importance, I was there to bear witness, and that's all that matters, really.

He left by going up the stairs to the right of the stage and proccessing - there is no other word - along the tables up there, shaking hands with the punters who'd paid to eat, or possibly VIP guests, I dunno. Meanwhile the band were playing uptempo "he's-not-quite-gone-yet-but-he's-going-and-it's-still-exciting"-type music. I couldn't tell whether there were more tables or punters in the space upstairs immediately opposite the stage - the music continued playing so I suppose so - but shortly after he was out of sight of my vantage point I thought: Well, why am I still here? I've heard Stand By Me and the rest; there won't be an encore as we've already had that mini "I'm going - oh, now I'm back almost immediately" bit. No one else was showing signs of moving but I went, submitting again to a vox pop thingy which I regretted. I didn't want to say anything negative but it wasn't quite the transcendant experience I'd hoped for.

I babbled in the pre-show vox pop about his lifting us and us lifting him. I wanted the intoxication, the blissful forgetfulness that some gigs offer and whether or not it was down to the noisy punter behind me I only got that intermittently. I was earthbound, assessing it, for too much of the time, and I'm not sure whether that's something inherent in me or to do with the gig.

Alright, it's me. I recently pressured a colleague into staging a celebration (of sorts) of a milestone at work and afterwards I thought to myself - meanly and selfishly - It's not enough. But nothing would be enough. In other words, short of Ben E King rewinding fifty years, or all the other ticketholders graciously bowing out so that I can commune with the great man on my own, I'm not sure what, if anything, would give me the nebulous satisfaction I seek. And I can't be that person who heard these songs for the first time, nor can I be the person who in 1987 brought a bottle of wine and a cassette of Ben E King: the Ultimate Collection to a certain door.

I'm glad he's around and still singing, and I was glad to sing along to Stand By Me. And I'm sure from what I've read that he is glad to spread happiness ... in fact, maybe that little bit of You Are My Sunshine added to the Stand By Me riff was the truest bit of Ben E King tonight. It was simple joy. And actually, it's just about submitting to it. Why don't I try that sometime, eh? Eh? But then I wouldn't be me. I would be the person below instead:

[Sadly you can't hear that person, as the Winkball site is down, but the gist of what she said was that King was like a much-loved member of the family who wasn't what he once was, but it didn't matter, because you loved him anyway - and she smiled throughout, without a trace of disappointment.]

Postscript: One of the mobile phone recordings has already (Saturday evening) been posted to youtube. Other clips are available of Thursday's gig but this is the one I saw. Unfortunately it cuts off before You Are My Sunshine, but it is still pretty good. So I have to say thank to one of the many who interposed their mobiles between themselves and the experience in such a selfless manner. Or something.

Those clips of the previous night have better audio - there is what sounds like some automatic recording level business kicking in and out at times - suddenly a bit muffled, suddenly all trebly and clear.

But I sort of like that, or at least it seems appropriate: a reminder that what is contained in a camera held aloft is not the experience itself but a souvenir. And even the abrupt cut-off seems right: go to see Ben E King for yourself, if you get the chance, to hear him sing the rest.

Or just let the music play on in your head, a memory of the record, or of the gig if you were there. Or of some other performance from the past fifty years, one of however many times now Ben E King has taken to a stage to sing those words and hear them echoed back:

[Okay, cue the repost tracing the origins of that song:]

Stand By Me

I can't remember when I first heard Stand By Me. It may even have been the Lennon reworking, as my earliest definite memory is of dancing to his version during one of the regular rock'n'roll nights at Tiffany's, Glasgow, in 1975, the enduring Rollin' Joe reassuring us (or himself): "John Lennon's coming home."

But not to have heard Ben E King first just seems wrong: Lennon's may be a great sound (and not one of the Rock'n'Roll album's Spector-produced tracks) but now I can't help hearing it as a cheerfully coarsened version of the original.

As ever, his voice has been treated in some way, and whatever the delights of that bombastic arrangement with its riffing saxophones and humorous guitar quotation, in a sense it's another aural disguise: beneath those two layers of padding Lennon's phrasing (as on just about every cover) has been copied from Ben E King's performance - which may say a lot about his love for the original but doesn't add anything essential to it.

Unless that's the point: if he's basically celebrating a memory, you could argue it's quite right that it should be bigger, louder than the original. And if rearranging places the emphasis on the song and King's voice (as echoed in Lennon's delivery) rather than Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller's production (one wonders at what stage Spector, the great pair's protege, knew of Lennon's plans to record it) the revamped version might even - who knows? - be closer in spirit to the initial idea which King brought to Leiber and Stoller.

King has said somewhere that all the pair (who have co-composing credits) really added to the song was that distinctive bassline, but he was shrewd or humble enough to realise that that was what helped make the record - and ensured his own immortality. (There are other reasons, too, which I'll come to later, why he might not have been minded to raise any objection.)

King's own record was first released in 1961, and since then it's never really gone away. Covers (including a so-so one by the then Cassius Clay and a bizarre Mike Yarwood version by Spyder Turner) apart, that same recording was a major hit again in America in 1986, thanks to the rites-of-passage film bearing its name. It took a jeans ad to propel it to Number One in Britain the following year, complete with cash-in compilation (actually a well-chosen selection of Drifters and solo tracks) bearing a still from the ad on its cover.

Did King consider such promotion of his classic infra dig? Probably not in the case of the film, as he participated in a promotional video for the rereleased single featuring its actors - and he has a famously easygoing nature anyway.

That video is an interesting one: an old TV clip of King lipsynching to his hit appears to be revealed as the illustration of a memory related by the modern day performer to a group of students in a lecture hall, unused instruments in the background; two of the film's young stars are cajoled out of that group into coming up and dancing alongside him, then after a few key shots from the Rob Reiner film the group has swelled into a crowd of young and old (the original listeners?) in an exterior location, united by their love of the song.

Well, it sure beats peddling jeans (though I do like the album cover's apocalyptic sky), and even if the promo blurs the line between anthem and cheery singalong it does at least say something about the universality and timelessness of the song. There only appear to be two black faces, each figuring briefly in closeup, among the listeners, which may be stretching universality a bit thin for a song I have seen claimed as a civil rights anthem, although I can't say I've come across much evidence online. They do seem carefully chosen, however: a young man whose presence in the lecture hall becomes more significant if we assume if we're back in the same time period as the film, and a young boy - hope for the future? - in the later crowd.

That double whammy of film and TV ad was undoubtedly a force for good in the sense that it gave King back some box office clout, enabling him (I hope) to ditch or limit the kind of gigs he had been reduced to - hotel ballrooms and dinner theatres - when interviewed around 1984 for Gerri Hirshey's book Nowhere to Run. "Not a man given to bitterness or soppy regret", he stresses he is making a nice living and can't complain, talking only of "adjustments" - although his frustration seems pretty clear:

That double whammy of film and TV ad was undoubtedly a force for good in the sense that it gave King back some box office clout, enabling him (I hope) to ditch or limit the kind of gigs he had been reduced to - hotel ballrooms and dinner theatres - when interviewed around 1984 for Gerri Hirshey's book Nowhere to Run. "Not a man given to bitterness or soppy regret", he stresses he is making a nice living and can't complain, talking only of "adjustments" - although his frustration seems pretty clear:"I find them [the audience] very, very hard to reach. Even as many times as I've played it, I still stand in the wings sometimes, and I look out at the audience for a while. They're like forty and fifty and sixty, and the drummer can't get but so loud. And the bass can't get funky. If I say 'funky' to them, I have to explain why I'm doing this."As described in one of the Doo Wop Dialog[ue] entries, it was around that time that I saw him perform in Glasgow, reunited with a cabaret-hardened version of the Drifters - an arrangement which Marv Goldberg says actually lasted for three years of UK tours. Perhaps symbolically, this was not at the legendary Apollo (the Harlem institution's Glaswegian namesake) but in the more sedate setting of the nearby Theatre Royal, home to ballet, musicals and the odd genteel touring theatre production. The support act was a comic, further emphasising the un-rock'n'rollish nature of the event. I wrote in that 2000 post of an onstage culture clash:

while the late Johnny Moore and the others were comporting themselves like so many manic starfish, projecting like crazy throughout, King sort of hugged himself as he quietly, naturally, sang his hits: "Hey, I can't be that person anymore," he seemed to be saying, "but this is as much as I remember. I'm not gonna embroider or patch it up, but what I tell you will be true for me now. If I made it any bigger, I couldn't feel it, so what would be the point?" And it worked; I remember the sense of him giving himself as a real person that night.That may, in part, be sentimentalising, as the voice I thought held in reserve may already have begun to lose some of its power, as had become more evident by the time of the 2001 Leiber and Stoller tribute gig; but that Gerri Hirshey interview still suggests that, whatever the setting, Ben E King will never stiffen into the Archie Rice of Soul. Nor has he salted away all his earnings: as will be discussed more fully later, King has never forgotten his roots and has set up a charity (Leiber and Stoller are honorary chairs) to fund music scholarships for students, among other things. (Listen to some of his most famous songs and learn more here.)

What makes Stand By Me so memorable? It's timeless but also a product of its time, the influences which shaped King and co-composers Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Following the trail to its origins even provides a kind of snapshot history of the development and interrelationship of gospel, doo wop and soul.

Benjamin Earl Nelson was born in Henderson, North Carolina, but moved to New York in 1947 at the age of nine, where his father ran a restaurant. For the young Benny, as Hirshey's book puts it, Harlem was

the strange cemented-over place [...] where amateur groups collected under corner streetlamps like sharkskinned moths. Sundays, he recalls, most of the boys sang in church, in storefronts and the solid brick-front Baptist churches that sat along Lennox, Seventh and Eighth avenues like watchful matrons. But until dawn delivered those sweet harmonies unto the feet of the lord, Saturday night bore a wave of voices tuned to the frequencies of earthly love.But despite the national success of doo wop by the time he was singing with his friends on street corners or on subway platforms where "you could hear the sound - your sound - coming right back at you, the way it might on a recording," he emphasises that for him it began as "a neighbourhood thing":

"And if you came up, like so many of us did, from the South, singing could help you get it all together. Turn you into a city boy, you know? I was in two groups most of the time. I sang with an R and B one, but I stayed with the gospel. I mean, for us it was no blasphemy, that kind of garbage. For me the feeling I got was the same. If it was an old church song, one of those old-timey Dr Watts hymns, or a new hit you'd been learning off the records, you took a song and made it your own. And your buddies, the guys who did it with you, they were your heart. You could get so in tune it seemed you all had but one heart between you. Man, you knew when all the other guys were gonna breathe."Nowhere to Run, a history of soul music told through interviews with the artists themselves woven together, as above, by Hirshey's narrative voice, is highly recommended. As mentioned in Doo Wop Shop posts, reading this book and finding details such the above inspired me to write a radio play about a doo wop singer - a composite character, but drawn in part from King's early days. No point in rehashing the whole chapter, entitled Uptown Saturday Night, here, but it's worth hearing about the specifics of those fabled streetcorner days from one who was there:

Benny catches himself for a moment and laughs, a little self-consciously. He wonders aloud if he isn't getting carried away by memories.

"No, no way," he decides. "I really mean it. I would say that those street years, in the groups, were the best of my life. Not the big successes, the gold records, looking at where you are this week in the charts, all that garbage. I mean, that was great, I loved it, and it's fed my family. But listen, it's just real hard to describe now the feeling a quartet gave you. You never felt alone, is all."

"We were pretty cool in my area. We had our fighting crowd - they were the Sultans, mean, ugly, bald headed dudes - and we had our singing crowd. I never really got into fighting. It drove me crazy to have to run like hell for five or six blocks when I could just as easily smile, and doowop, and duck around a corner."Nor was that Chicago group's influence confined to America:

Vocal groups sacked and pillaged, but in a mannerly way.

"My buddies and I would walk from a Hundred Sixteenth to maybe a Hundred Twenty-ninth. And on those blocks alone you'd find anywhere from three to five groups. We'd stop and listen, and if we felt we were better we would challenge them. It was territorial, you know, and you'd have to go out looking for the competition," Benny says. "You'd stand around and check it out; they'd have a crowd anyhow. And their girls of course."

To the victors went their phone numbers. Friday and Saturday nights were the most popular for such musical marauding parties. And no challenge was issued without great preparation.

"We'd learn from the records like everyone did. The group to get you over the best would be someone like the Moonglows. If you could sing Moonglows, you could kill the neighbourhood. They had great harmonies, the Moonglows. Or the Satins or the Clovers. We tried to pattern ourselves after the tight-harmonied groups."

Even in the slums of Kingston Jamaica furture reggae star Bob Marley drew his early inspiration from the Moonglows. There was something about this sound, especially the Moonglows' tight, chesty "blow" harmony, that had tremendous appeal in the post-big band era.Perhaps it's because a 1955 Chess recording provided a kind of stepping stone from the more old-fashioned tones of established black vocal groups like the Inkspots to gospel-inflected doo wop.

In The Heart of Rock and Soul Dave Marsh notes that

For most of its length "Sincerely" might as well be a record by the Mills Brothers or the Ink Spots [...] Only the "vooit-vooit" in the background and a bluesy guitar lick hint that something different might be going on. But, at the conclusion of each verse, the arrangement swings into something more like gospel. This oscillation between church singing and the formalities of Tin Pan Alley-era pop is crucial to the entire ethos of doo wop [...] Sincerely is [...] poised [...] on the fault between profound musical changes.The moments Marsh is talking about leapt out at me, though I wasn't then able to identify what was going on, when I first heard the song around 1978 on the soundtrack album for the Alan Freed biopic American Hot Wax:

But I'll never, never, never, nev-ahhh! Le-het her go...Now I know that Sincerely can be hailed both as a great record and a fine, fine, superfine bit of commercial calculation. The Moonglows were not an Inkspots-type group who had suddenly found a little unexpected fire in their bellies; their earlier sides on the Chance label show they had always alternated ballads with bluesy jumps and wild, gospel-derived singing (2.19 Train, for instance). Bringing the two sides together - and deciding just how much of each to include - was the innovation and the gamble which paid off bigtime.

Talking of paying off leads back to Alan Freed, the legendary and influential DJ whose name not-so-mysteriously appeared on the credits for Sincerely alongside that of Harvy Fuqua; it won't be the last time the issue of composer credits comes up in this piece.

But Freed seems, at least, to have loved the music, and there is a widely held belief that he was made a scapegoat for the payola scandal from which Dick Clark emerged unscathed. If you can afford to buy the DVD box set version of Hail! Hail! Rock'n'Roll!, Taylor Hackforth's Chuck Berry documentary, the superb extras constitute a history of rock'n'roll in themselves, including raw footage of a conversation with Chuck, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Both Little Richard and Chuck - and do remember this is Chuck Berry we're talking about - speak with immense fondness about Freed.

But Freed seems, at least, to have loved the music, and there is a widely held belief that he was made a scapegoat for the payola scandal from which Dick Clark emerged unscathed. If you can afford to buy the DVD box set version of Hail! Hail! Rock'n'Roll!, Taylor Hackforth's Chuck Berry documentary, the superb extras constitute a history of rock'n'roll in themselves, including raw footage of a conversation with Chuck, Little Richard and Bo Diddley. Both Little Richard and Chuck - and do remember this is Chuck Berry we're talking about - speak with immense fondness about Freed. Er, just to reiterate, in case you didn't quite hear me: that's Chuck Berry, the man obliged to share composing credits of Maybelline with Freed and one Russ Fratto; the man who doesn't walk onstage till the money is on the table or in a stuffed briefcase - or, ideally, a stuffed briefcase on the table. And it was Berry, playing himself in the biopic, as I'm sure I must have mentioned somewhere here already, who said those most magical and unlikely scripted words when told the promoters would be withholding his fee for a Freed concert: "Guess I'll play this one for rock'n'roll." Now that is acting. (When Berry played the Glasgow Apollo in 1975 my Town Hall humiliation brother, then a student reporter, compounded his reputation for egregious gaffery by approaching Berry's management for an interview without proffering a fistful of fivers.)

Incidentally, it is often claimed that Ben E King actually joined the Moonglows. I enquired about this on the Doo Wop Shop board when revising a talk on Stand By Me for my last hurrah as dominie wannabe. In response, someone kindly emailed the transcript of a radio interview with the great man: Benny, it seems, did hang out with the group for about six weeks to get a sense of what they did but eventually realised (this is all from memory) the Moonglows' style meant that even when singing lead his voice wouldn't be spotlighted the way it might in another group - which tends to suggest that for all the self-effacement he had a pretty sure sense of his ability even then.

Presumably this took place some time between coming second at amateur night at the Apollo (Harlem) in 1957 with his local group the Four B's ("Three schoolmates who used to sing around doing harmonies") and being recruited in 1958 for the 5 Crowns by their manager Lover Patterson, as King recalls in this interview with Gary James.

But he wasn't standing around idly in the interim: the Apollo success seems to have propelled him towards the realisation that, with what seemed like "hundreds of groups and a thousand street-corner versions of Earth Angel and Sincerely," the work to make his mark had only begun.

This was to include tuition from the great Cholly Atkins, then a freelance coach, who had already helped the Cadillacs ("So sharp it hurt") perfect their dance moves.In his autobiography Class Act Atkins, later an integral part of Motown's success, explains that choreography for doo woppers was about ensuring longterm survival:

Being asked to join the 5 Crowns proved a particularly lucky break for Benny. Drifters' manager George Treadwell had just fired the remnants of his group (Unca Marvy has details) and needed a new set pronto. King and his new group agreed to step into their shoes - and for many it's this Mk. 2 version which are the - I was going to say "real", but as that's such a contentious issue where the Drifters are concerned, let's settle for the most fondly remembered version of the group, rather than the Clyde McPhatter era Drifters or the UK-revived early seventies hitmakers led by veteran Johnny Moore.Right from the beginning, my ultimate goal with the Cadillacs was to change them into a standard act. At that time, a vocal group was only as good as its last record. If it didn't have a hot record, it wasn't worth too much to the promoters. I wanted to help them make the transformation from rock-and-roll singers into versatile performers, so they would have a wide range of venues available to them.

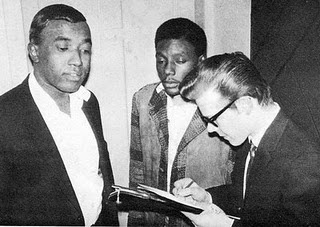

Such broad divisions scarcely seem adequate for a group which must have had over fifty singers pass through its ranks by now; one can understand if Bill Millar, author of a 1971 book about the group, continually puts off work on a revised edition likely to be out of date before it hits the shelves. (Is there a website devoted to this Sisyphean task?) Not to mention the questionable legitmacy of lots of Drifters, er, variants which could be discussed at length ... Millar is pictured, below, doing his own sleuthing; as an Australian blogger notes: "he looks like a chap who's not going to give up till he nails the matter, no matter how discomfited his subjects may be."

But as determining where the Drifters end and "tribute" acts begin could addle any brain other than the mighty Millar's, and as we have a song to aim towards, better to concentrate on the fact that Ben E King and his fellow Crowns (the new moniker an allusion to the group name?) were not themselves expected to function as a glorified tribute act to McPhatter's old group, and instead were given fresh material to record from the best of the Brill Building writers including Leiber and Stoller, their initial producers.

"It all came together in Clyde," Benny says [pictured with McPhatter, above, in 1972]. "He could sing the blues, but he had that gospel sound since he came up in church. What Clyde did was to bring gospel into pop in a big way as a lead singer. I guess you could say he made a wide-open space by mixing it up like that. A space a lot of guys were grateful for."

This is a sentiment echoed in Owen McFadden's BBC radio series on doo wop, Street Corner Soul, where more than one interviewee says something to the effect that while they liked Sonny Till, McPhatter (below, in his pomp) had the whole package: voice, babe-magnet good looks and excitement; they admired Till's voice but they never actually wanted to be him.

The conclusion of Millar's book, written when Clyde McPhatter was still alive and had hopes of reviving his career, succinctly sums up the importance of his contribution to the development of doo wop:

The conclusion of Millar's book, written when Clyde McPhatter was still alive and had hopes of reviving his career, succinctly sums up the importance of his contribution to the development of doo wop:

McPhatter took hold of the Inkspots' simple major chord harmonies, drenched them in call-and-response patterns and sang as if he were back in church. In doing so he created a revolutionary musical style from which - thankfully - popular music will never recover.

And if you seek his monument, try listening to the restrained hysteria of The Bells, a possible influence on King's vocal in Stand By Me ...

... or place the Ink Spots' and the Dominoes' versions of When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano side by side.

Aaron Neville, quoted on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's page on McPhatter, inducted in 1987, said:

Anything Clyde sings is a prayer. When I was growing up, I don’t care what else was going on in the world - Jim Crow, all the other stuff - you could put on Clyde McPhatter and it would all disappear.Whatever McPhatter's stylistic innovations, however, by the late fifties increasingly sophisticated production techniques were encouraging wider change: it was the sound of a record which sold, not its fidelity to the artist as heard live. King's first lead in 1959 with his version of the Drifters, There Goes My Baby, is of considerable historical significance in this respect:: like Sincerely, it has a foot in two camps.

Incidentally (again), Charlie Thomas, the intended lead, either got the studio equivalent of stage fright or couldn't pick the song up quickly enough from Benny to satisfy Leiber and Stoller (like Stand By Me the composition is credited to all three) and King was eventually asked to take over - an historical moment in itself, as according to an "audio biography" on the CD issue of The Beginning of It All he hadn't thought of himself as a lead singer until then - which makes my memory of his Moonglows-related interview less reliable.

King, forced to sing at the top of his range, delivers a great gospel/doo wop lead and the rest of the group are doing the usual doo wop type backing, but that arrangement is something else. It came about because a recording session with Leiber, Stoller and arranger Stanley Applebaum was falling apart so they started to "fool around", as Jerry explains in an interview quoted by Millar:

Stanley wrote something that sounded like some Caucasian take-off and we had this Latin beat going on this out of tune tympani and the Drifters were singing in another key, but the total effect - there was something magnetic about it.Leiber and Stoller played the tapes back to Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler; Wexler famously spat out his tuna sandwich in disgust but Ertegun bowed to the producers' insistence that there was something amid the mess - and the song proved a huge hit - even if Leiber himself, hearing it later on the radio, was "convinced it was two stations playing one thing." (Millar observes that Leiber may have meant one station playing two records as "the effects were multi-dimensional.")

Strings were not entirely new in rock'n'roll or doo wop. Since I Don't Have You had come out with a luscious arrangement the previous year, making the Skyliners the first white group to top the R&B charts (and provide a hint or two for the young Phil Spector) but they were the exception. As Millar says:

The strings on There Goes My Baby were not the dull, weepy violins used on popular recordings by white singers for the past twenty years. They rose and fell with a stark, triste and postitive allegiance to classical music. With justification the song might have been called There Goes Tchaikovsky. Kettle drums pounded throughout, but more obviously during the deeper, quieter moments of the string passages, strengthening a reseemblance to the 1812 overture. It is an interesting coincidence that, like the works of the Russian composer, There Goes My Baby can also be described as "notable for a vivid, forceful scoring and for an often expressed melancholdy." Ben E King sang in a higher key than his normal baritone range. The effect was two-fold: it heightened the coarse, untrained, root-gospel quality of his voice and imparted an air of hopelessness to the theme of the song.

[...] There Goes My Baby was instrumental in bringing the Drifters from the comparative obscurity of the large but segregated black commnunity into popularity in over half a million white homes. For an inexperienced but inglorious group, The Crowns had it made. They bowed daily in the direction of The Atlantic Record Corporation for ever more.

Which may provide another reason why King immediately understood the signiificance of Leiber and Stoller's contribution to Stand By Me. It's not too difficult to reimagine There Goes My Baby as a straight doo wop record, on some little indie label, a local hit, perhaps; it needed the happy discovery of that astonishing setting (dubbed "beat concerto" by the music press), to achieve crossover success, even though others may feel, as I do, a certain sadness in acknowledging the greatness of this production. Its influence helped spell the death knell for a simpler era of recording where the overall sound was less important than the thrill of hearing four or five voices blending together.

Still - it's gone. As my Cheapo gaffe friend's nephew would say: face it. There Goes My Baby, like Stand By Me, looks forward to soul and, ultimately, the Motown assembly line approach. And it was another brick in Uncle Phil's Wall of Sound, as according to the Rolling Stone Encyclopedia "Phil Spector studied this production model under Leiber and Stoller, working on The Drifters' records"; perhaps, indeed, that was the 45 which inspired Phil's vision of "little symphonies for the kids," even if it was Wagner he cited rather than Tchaikovsky.

But it's not simply the sound of There Goes My Baby which prefigures soul: the song itself, the starkness of such lyric as there is, feels a world away from the "well-worn satchel of cliches" (the Encyclopedia's description of Come Go With Me) which can make up a doo wop record. But the tone doesn't quite match that of non-crossover rhythm and blues songs either, leavened as they often are with a knowing wit, a worldliness; it's closer to a rawer, earlier blues.

Or gospel.

By the mid to late 50s, artists like Ray Charles and Sam Cooke were beginning to realise there was a lot to learn from the stripped down language of gospel songs as well as the singing which McPhatter had already introduced to a wider audience. They developed a new kind of music, with words cut to the bone, giving the singer space to linger over them, put more of himself into the performance: what was to become known as soul music.

Some say that There Goes My Baby is the first soul record; others go back to Ray Charles' I Got a Woman (1954), based on a gospel song; Charlie Gillett (author of the first serious study of Rock'n'Roll, The Sound of the City) has pointed out that the horns on this record are effectively doing the job of backing singers in a gospel quartet.

Sam Cooke was in a particularly good position to develop this new form, having been a professional gospel singer for years (in the Soul Stirrers, yet), singing songs as stark as Pilgrim of Sorrow, whose origins date back to the days of slavery:

Lord I'm poor pilgrim of sorrowIn the same way the opening of Stand By Me is simple but disturbing in what it conjures up:

Down in this world I'm all alone

I have no hope for tomorrow

And I have no place that I can go

[...]

Sometimes I'm both tossed and driven

Till I decided that I would roam

That's when I heard of a city called Glory

And tried to make that city my home

When the night has come and the land is darkThere's nothing to link that experience to any time or place - there's only desolation. It goes on:

I won't be afraid just as long as you stand by meThe singer is addressing his lover but from the context it could just as easily be his God. As in many gospel songs, the imagery is from the bible:

If the sky that we look uponThis would appear to come from Revelations - Saint John's description of the wicked being punished at the end of the world:

Should tumble and fall

And the mountains should crumble to the sea

a great mountain burning with fire was cast into the seaNote how, by the addition of a few specifics, Ira Gershwin renders a similar image comic and harmless:

In time the Rockies may crumble, Gibraltar may tumbleThough I suppose the absence of imminent catastrophe in the G-Men's loved-up ditty also helps.

They're only made of clay

There's some truth in the generalisation that the pioneers of soul music would more or less just change the odd "God" to "girl" in a gospel number to be rewarded with an instant hit. Under the less-than-opaque pseudonym of Dale Cook, Sam Cooke amended the Soul Stirrers' Wonderful ("My God is ...") to Loveable ("My girl is..."); Ray Charles's This Little Girl of Mine, later covered by the Everly Brothers, was originally This Little Light of Mine. (I wish I could remember the recording of This Little Light which Alexis Korner, narrating a BBC radio documentary about the Rolling Stones, played after a section describing the death of his friend Brian Jones.)

Could the spareness of Stand By Me mean that it, too, is just a gospel song in disguise? The answer is not entirely straightforward. Ben E King's song does ultimately derive from a 1905 gospel number of that name but it's far from being a simple copy, even though some websites seem to assume the songs are one and the same.

The first Stand By Me was written by Charles Albert Tindley, a man who has been called one of the founding fathers of gospel music, immediately preceding the more well known Thomas A. Dorsey: Tindley died in 1933 and the song which established ex-bluesman Dorsey's gospel reputation, Precious Lord, was written in 1932.

Tindley who taught himself to read and write, took a correspondence course in theology and eventually became pastor at the church where he'd once worked as janitor. But that bare account ought to be fleshed out with this detail from the Christmas Songbook website:

Tindley grew up in extreme poverty and oppression. After his mother Hester Miller Tindley died, his father was forced to rent out Tindley's labor:An article by C. Michael Hawn (including information about We Shall Overcome, also indebted to a Tindley original) is readable in full here. Below are the complete words of the first Stand By Me plus Hawn's commentary:

"It therefore became my lot to be 'hired out,' wherever father could place me. The people with whom I lived were not all good. Some of them were very cruel to me. I was not permitted to have a book or go to church. I used to find bits of newspaper on the roadside and put them in my bosom (for I had no pockets), in order to study the ABC's from them. During the day I would gather pine knots, and when the people were asleep at night I would light these pine knots, and, lying flat on my stomach to prevent being seen by any one who might still be about, would, with fire-coals, mark all the words I could make out on these bits of newspaper. I continued in this way, and without any teacher, until I could read the Bible without stopping to spell the words."

When the storms of life are raging,For a detailed account of the transition from spirituals to gospel, and the roles played by Tindley and Dorsey, read The Gospel Truth about the Negro Spiritual by Randye Jones here.

Stand by me (stand by me);

When the storms of life are raging,

Stand by me (stand by me);

When the world is tossing me

Like a ship upon the sea

Thou Who rulest wind and water,

Stand by me (stand by me).

In the midst of tribulation,

Stand by me (stand by me);

In the midst of tribulation,

Stand by me (stand by me);

When the hosts of hell assail,

And my strength begins to fail,

Thou Who never lost a battle,

Stand by me (stand by me).

In the midst of faults and failures,

Stand by me (stand by me);

In the midst of faults and failures,

Stand by me (stand by me);

When I do the best I can,

And my friends misunderstand,

Thou Who knowest all about me,

Stand by me (stand by me).

In the midst of persecution,

Stand by me (stand by me);

In the midst of persecution,

Stand by me (stand by me);

When my foes in battle array

Undertake to stop my way,

Thou Who savèd Paul and Silas,

Stand by me (stand by me).

When I’m growing old and feeble,

Stand by me (stand by me);

When I’m growing old and feeble,

Stand by me (stand by me);

When my life becomes a burden,

And I’m nearing chilly Jordan,

O Thou “Lily of the Valley,”

Stand by me (stand by me).

Life was not easy [writes Hawn] for many members of Tindley's congregation during the industrial revolution of the northeastern United States at the turn of the 20th century. The opening stanza of this comforting hymn draws upon images from a narrative found in three of the Gospels in which Christ rebukes the winds and stills the raging waters.

Later stanzas painted a realistic picture of life's struggles through apocalyptic references such as "in the midst of tribulation," the "host of hell assail," and "in the midst of persecution."

In the final stanza, "Stand by Me" ultimately provides the assurance that Christ has the power to overcome all suffering on earth. Comfort will finally come as we approach "chilly Jordan" though Christ, the "Lily of the Valley."

One of my biggest surprises when originally researching the song's origins in the mid nineties - those faraway times before the net put all sorts of information a click away - was hearing, through a set of headphones at the National Sound Archive in Kensington, a recording of the gospel original by Elvis Presley.

It's not a full, nor a fully logical, rendition - we get the first verse plus two half-verses shunted together - but it is, nevertheless, an astonishing performance: vulnerable, unshowy, straight from the gut, backed only by a piano, the Jordanaires and some barely heard female singers, which can make you forgive the erstwhile Memphis Flash a great deal (except, perhaps, an execrable, possibly looped, nine-minute version of Don't Think Twice, It's Alright). And no need for Phil's little symphonies when the resonance of that piano fills the studio, an orchestra in itself; it even seems to echo the "raging" of the first verse. Dunno about John Lennon, but listening to this 1967 recording - for me among his finest two and a bit minutes - it sure as hell sounds like Elvis is steaming home.

But that lesser-known example of the musical cross-pollination which defined Presley's career steers us back to murkier waters. Sad to report that the song is "adapted and arranged by Elvis Presley" and credited solely to his music company in at least one songbook: it's one thing to fleece those who choose to be fleeced ...

I was going to add something like: "Still, all part of that other great tradition of making money out of a cut-and-shut job", but on reflection it doesn't do to become too sanctimonious in this area, as the more I learn about the development of popular music in the twentieth century once records and the radio kicked in, the more I realise that just about everything was up for grabs and that the terms theft, inspiration and homage are mere cultural constructs, more or less interchangeable (always provided Morris Levy Can't Catch You).

Which brings us to Exhibit B: a gospel song, written one year before King's, entitled Stand By Me Father. Credited to Sam Cooke and his manager, JW Alexander, it was recorded by Cooke's former group the Soul Stirrers; Cooke produced but did not sing.

This song was also inspired by Tindley's 1905 original but also draws from the common stock of gospel/spiritual imagery, specifically those biblical accounts of miraculous escapes such as Daniel from the lions' den and the Hebrew children from the furnace.

The rest of the group appear to answer "... me, lord" after each "Stand by", so the full phrase is there. It's hardly a wildly original composition in itself but the big question is: is the repeated refrain of "Stand by me" close enough, musically, to Ben E King's recording to be able to say that King "borrowed" it?

Oh father, you've been my friendPreparing my talk in 2001, I wrote: "My feeling is that King is quoting from Cooke - consciously or unconsciously." Well - it was conscious. Thank you, World Wide Web, where this page of BBC Radio 2's website has audio of King confirming:

Now that I'm in trouble

Stand by me to the end, oh lord

I want you to stand by

Stand by

Well

All of my money and my friends are gone

God I'm in a mean world

And I'm so all alone, oh lord

I need you Jesus

Stand by

Stand by

Well

They tell me that Samson lived in ancient times

I know that you helped him kill 10,000 Philistines, oh lord

Whoa I need you

Stand by

Stand by

Here's another thing

They tell me that they put Daniel

Down in the lion's den

I know you went down there father

You freed Daniel once again

That's why I said, oh lord

Do me like you did Daniel,

And stand by

Stand by

Well

Sometime I feel like the weight of the world is on my shoulders

And it's all in vain

When I begin to feel weak along the way

You come and you give me strength again

The Hebrew children went in a fire

Ten times hotter that it ought to be

Just like you delivered them father

I know you can deliver me, woah Lord

I'm calling you Jesus

Stand by

Stand by

When I'm sick father

Stand by

When the doctor walk away from my bedside

Stand by me, father

When it seem like I don't have a friend

I wonder will you be my friend

Stick closer than my brother

Stand by

Stand by

I took Stand By Me from an old gospel song that was recorded by Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers called, I think it was, Lord I'm Standing By, and I kinda snuck that "stand" bit out and I started writing and the song more or less had written itself ...King appears to be confusing God Is Standing By and Stand By Me Father. Both were both recorded by that later version of the Soul Stirrers - Johnnie Taylor doing a pretty convincing Sam on lead - for Cooke's shoestring SAR label, a pet project he pursued alongside his hitmaking duties at RCA. God Is Standing By is credited to Johnnie Taylor.

Listening again, however, the bassline of God Is Standing By sounds not unlike the one which powers the recording of Stand By Me - so could what happened in the studio in 1961 have been a conflation of the two SAR recordings? But that would take Leiber and Stoller's rhythmic backbone, a contribution readily acknowledged by King, out of the frame, so probably not, unless that beat was just something in the air: there was certainly a craze in New York for Latin American music at the time, athough Leiber and Stoller claim specific credit here for introducing the Brazilian baion rhythm, later taken up by Burt Bacharach and Phil Spector, to pop:

And the first record they used it on? There Goes My Baby."We first heard it a few years before on a soundtrack album," says Stoller, "and filed it away for future reference.""The great thing about it," continues Leiber, "was that it was so attractive and so insistent, like Ravel's Bolero. Before that, whenever we did a slow ballad it fell apart, it would get boring. But the baion was a way of imposing a rhythm on the bottom of a slow ballad, so it kept going.Burt Bacharach worked for us in the early Sixties. He learnt the baion from us and he used it his entire life. All those great Dionne Warwick songs? That's the baion. It is indestructible; that's why we used it so well and so often."

I don't know whether the beat of Stand By Me is technically a baion, although it certainly seems Latin American, and its function appears to be precisely as Leiber describes above: Stand By Me keeps going, alright. In Leiber and Stoller's autobiography Hound Dog (quoted in this review), Jerry Leiber goes so far as to say:

The lyrics are good, King’s vocal is great. But Mike’s bass line pushed the song into the land of immortality. Believe me — it’s the bass line.A fair assessment? Shorn of its symbolic significance, the 1966 cover by Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali) demonstrates what happens when you keep the bassline but lose the voice.

Incidentally, on the BBC page above, King says that the "scratching sound" was not produced by a guiro, even though that's the instrument seen in the 1986 promo:

What they had done, they taped over the snare drum and the wire bits on the end underneath the snare drum is the scratch noise.There are some contradictions in King's and Leiber and Stoller's accounts of the recording of Stand By Me. King says that Stand By Me was recorded at the end of a session (widely agreed to be the case) but that, being unexpected, it was a head arrangement. King may have thought this was so, but as mentioned in another entry I had the chance to ask Leiber and Stoller directly during an audience Q&A which followed the premiere of a 2001 documentary:

Q: How unfinished was the song Stand By Me when Ben E King brought it to you, did you make the arrangement on the spot?Nevertheless, it has to be noted that Leiber and Stoller were recalling events of forty years ago at the time, so who can tell, as we approach the recording's fiftieth anniversary, precisely what the truth is? It may also be that the newly solo King, surrounded by the panoply of musicians and singers, was too wracked by nerves at being put on the spot and having to deliver to be able to take everything in; I would need to see it again but I vaguely remember his talking in the documentary about similarities with the There Goes My Baby and Stand By Me sessions: all the imposing set up then suddenly it's all down to him and he has to go for it. [I may revise this passage once I have seen the documentary again.]

MS: Well, the song wasn't finished when he brought it in. However, it was totally finished before the recording session took place. That's a figment of somebody's imagination, because the arrangement... the bass line I created for it, was picked up and played by the strings, it had bass and guitar playing from the top, and it was a fully orchestrated piece. As was Spanish Harlem. It was the same session. It turned out to be three and a half hours, and what Jerry was referring to [in the documentary] about the half-hour overtime, was that Atlantic was complaining about spending the extra money on this first session for Ben E King as a solo singer. It proved to be worthwhile to them - they had two smash hits.

JL: And one other thing, we never went into a session where every note of the orchestration wasn't written down and in triplicate, so it could be changed quickly. Everybody who could write had a copy of it. We were very well organized.

The review of Hound Dog referred to above also discusses some conflicting details reported in various books including Ken Emerson's Always Magic in the Air and Toby Creswell's 1001 Songs. Commenting that "collaboration is a messy business" the reviewer adds:

It’s worth noting that one-third of “Stand by Me” is a valuable thing. BMI reports that it was the fourth-most-played song on American radio and TV in the 20th century.Which, along with that bit "kinda snuck" out of Stand By Me Father, may be another reason for King's acceptance of the situation. On the issue of borrowing vs stealing, however, that "snuck" doesn't sound like any kind of shameful confession, especially when he talks of Stand By Me "more or less" writing itself: a song which demanded to be brought into being - and immediately felt like it had been around forever.

Revising the above, I came across an odd coda to the affair: God Is Standing By, the Johnnie Taylor composition which I thought King had confused with Stand By Me Father, was remade into a soul song called I'm Standing By. It was recorded, with the same bassline as the gospel side, by one Ben E King in 1962. It is credited to Taylor plus Jerry Wexler and Betty Nelson, who is Ben E King's wife.

Betty Nelson also wrote Don't Play That Song: she had been listening to Stand By Me, told Benny she had an idea, which he first ignored ("She's always got an idea") then encouraged her to take it to Atlantic, where she worked on it with Ahmet Ertegun, resulting in another big hit for her mocking husband.

Basslinewise, however, there's no denying that (like this blog entry) it's Stand By Me Pt.2. One wonders how Mike Stoller felt - although he may have been pacified (or piqued?) when Aretha Franklin's remake was a big hit with an entirely different underpinning - and I won't go into its piano intro which always makes me think of the (Cooke-era) Soul Stirrers' Were You There, a hard gospel style version of a spiritual ... Confusingly, in his "audio biography" King says that Don't Play That Song was "her one contribution to music - after that she just folded up," so I don't know where I'm Standing By fits into the picture.

Seductive, or maddening, though such internet sleuthing may be, the precise apportioning of the authorship of Stand By Me is less important than considering what is unique to the 1961 song. It may draw from King's gospel roots but it's not a gospel song. In terms of message, Tindley's orginal and Cooke's Stand By Me Father have far more in common. Both are (at least in one sense) upbeat: whatever life throws at you, you can depend on a God with a proven track record of helping those who have faith.

King's lyric is saying something different:

No, I won't be afraid, oh, I won't be afraidHe's hoping for support, not certain of it - and the way he hesitates between words emphasises the idea that he doesn't actually know who or what he can count on should disaster strike. There's no God in this Stand By Me - only the possibility of kindness from another human being.

Just as long as you stand, stand by me

Drawing, perhaps, from Clyde McPhatter's balance of control and hysteria, King's vocal is the equal of its surroundings: he claims he won't cry, although his voice seems on the verge of tears; and as the arrangement builds and the violins and cellos play that riff more insistently it's as though they're out to expose the fear and anxiety he's trying to deny - and much as I love those earlier, simpler doo wop recordings, I have to admit that the arrangement here is no mere garnish but integral to the record's effect.

But where does that anxiety come from, exactly? It may have been hijacked for a tale about boyhood friendship and all manner of other things but this is a song about a man who's afraid of being deserted by his lover ("Darling"). You'll find the same feeling, however, in many gospel songs and, especially, spirituals: the outsider down in this world all alone, feeling like a motherless child a long way from home. There is one solution for the poor Pilgrim of Sorrow - but there's no convenient City Called Glory in the secular landscape of blues songs, which nevertheless explore similar themes: not belonging; searching for something which, it seems, can't be found in this world.

Not too difficult to work out why a sense of alienation keeps recurring in African Amercian music. And it's worth remembering both that Ben E King grew up in the South and that Stand By Me was released in 1961, the year of the brutality against the Freedom Riders in Montgomery, Alabama. It would take another three years before a Civil Rights act was finally passed outlawing all forms of segregation. In the Land of the Free, music had been one of the few relatively undhindered outlets for black expression so it's hardly surprising that a sense of something fundamentally wrong with the world should be reflected in so many songs, even if direct protest had had to be coded in the past. You can bet that listeners to spirituals would have seen a double meaning in stories of people escaping from lions and fiery furnances. And the City called Glory could be heaven but could equally be freedom in the North, as in the spiritual which entreats the listener to Steal Away.

In yet another example of the strange cross-fertilisation which characterises popular music, when he joined RCA records Sam Cooke may have been freighted with all he had sung and learnt in the Soul Stirrers, and may have used that, often to to great effect, on numbers like Bring It On Home To Me, a duet with fellow ex-gospeller Lou Rawls (Pilgrim Travellers), but according to Peter Guralnick's biography it took a Bob Dylan song to spur him into creating A Change is Gonna Come: hearing Blowing in the Wind, he was apparently ashamed that no African American had as yet written his own Civil Rights anthem. I also note, on the site linked to above, that "He wrote the song after he spoke with sit-in demonstrators in Durham, North Carolina in May 1963 after he did a show there" - a mere forty miles from the place where Benny spent his early childhood.

I was born by the river in a little tent

Oh and just like the river I've been running every since

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

It's been too hard living but I'm afraid to die

Cause I don't know what's up there beyond the sky

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

I go to the movie and I go downtown

Somebody keep telling me don't hang around

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

Then I go to my brother

And I say brother, help me please

But he winds up knocking me

Back down on my knees

Ohhhhhhhhh.....

There been times that I thought I couldn't last for long

But now I think I'm able to carry on

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will

Listening to it ought to be enough to inform, or remind, you that this was Cooke's masterpiece, a final, perfect blend of all the lessons he had absorbed on either side of the gospel/pop fence. But there are several things particularly worth pointing up in the context of the themes covered in these two posts,

First, note the masterly way he moves from the gospel-type spareness of the opening (running like the river) to the specific detail of either being refused admission at a cinema (or being moved on afterwards?) which makes it unnecessary to spell out that the "brother" to whom he then goes for help is white.

And as in King's Stand By Me, there may be no God ("I don't know what's up there"), a particularly painful detail for black gospel fans who had already felt a deep sense of betrayal when Cooke crossed over to pop. And it wasn't the first time they'd had salt rubbed in their wounds, as Dave Marsh notes in his critique of Bring It On Home To Me. The gospel music community felt ripped off, he suggests, not simply through the perceived debasement of their music:

that wouldn't have been so bad, if the new wave of gospel-trained pop singers hadn't also stolen from gospel its poetry, whence stems so much of its power. From a fundamentalist Christian point of view, Bring It On Home to Me actively blasphemes, for Cooke declares himself a slave of love rather than a slave of God, and compounds the felony by usuing hymnal imagery to put the idea across.One can only imagine how they felt when Cooke went on to deny, or at least doubt, his God in the later song.

But the record is a mightily seductive one, which brings me to my second point. To grasp the significance of A Change Is Gonna Come, you could do worse than look at the list of musicians (below).

That list says a great deal about Sam Cooke's power at RCA by that time: their biggest-selling performer after esteemed gospel composer E.A. Presley. We're talking a full-blown orchestra, not a couple of violins - indeed, the original drummer was apparently so intimidated by the sight that he quit, leaving Earl Palmer to do the honours. Cooke apparently gave "rare freedom" to Rene Hall to arrange it, and if odd moments now seem a little sweet for those brought up on the tartness of Leiber and Stoller and George Martin, Hall knew exactly what he was about: smuggling a message into as many homes, black and white, as possible, and if that meant a little sugar coating, so be it ...

Chuck Badie... although the "I go to the movie" verse was cut for the single release.

Israel Baker - violin

Norman Bartold - guitar

Harold Battiste

Arnold Belnick - guitar

Louis Blackburn - trombone

John Ewing - trombone

Harry Hyams - viola

René Hall - guitar

William Hinshaw - french horn

William Kurasch - trumpet

Irving Lipschultz - violin

Leonard Malarsky - violin

Alexander Neiman - viola

Earl Palmer - drums

Jack Pepper - violin

Emil Radocchia - marimba, tympani, percussion

Emmet Sargeant - cello

Ralph Schaeffer - violin

Sidney Sharp - violin

Darrel Terwilliger - violin

David Wells - trombone

Clif White

Tibor Zelig - violin

And finally, Cooke's voice on this recording. It has been said that Sam Cooke sang with more passion to his God, on those early fifties Specialty recordings, than he ever did to his girl. It's a good line, and there are certainly songs where you get a strong sense of his holding back for commercial reasons, especially those early attempts at pop like I'll Come Running Back to You, whose sweetening of white female backing singers so sickened Specialty owner Art Rupe that he allowed his greatest asset to leave the label, taking his pop masters with him in exchange for relinquishing all rights to his gospel output.

But Cooke's performance on A Change Is Gonna Come may have been enough to satisfy even Rupe: no backing singers of whatever colour, and a vocal which achieves the perfect balance of control and emotion.

I have to admit that when first immersed in the Specialty gospel recordings, Cooke's singing on A Change ... struck me as tame in comparison to his gospel highlights like Touch the Hem of His Garment, or Were You There? Now, however, I can appreciate all that reined-in passion.

I have read that director Peter Hall, when working on a Pinter play, would encourage his actors to let it all out, all the anger and rage, in the early days of rehearsal (sometimes to Pinter's discomfort). But then at a certain point he would say remember all that, but now sit on it.

It would then inform a more restrained performance, which is what I think is happening with Cooke here. You only have to hear the posthumously issued Live at the Harlem Square Club to know that he retained that gospel power in the RCA years - but he was never, in any case, trying to emulate the likes of sometime Soul Stirrer and famed throat-shredder June Cheeks (whose New Burying Ground, with the Sensational Nightingales, is a stone classic).

A much-bandied quote is that Sam didn't want to be "that deep, pitiful singer", preferring to win hearts and minds by subtler means. Someone else described Cooke's voice as a blend of sandpaper and honey; the honey's important.

And to make the distinction between those songs which bookend Cooke's pop career absolutely clear: A Change ... is, for me, the steely sound of power in reserve; I'll Come Running Back to You sounds more like someone trying to work out what people want instead of trusting his own experience to tell them what they need.

All of which may inform Stand By Me but, again, has shifted our focus. I'm not suggesting that a geographical coincidence means that Ben E King's song is necessarily political in intent, like Cooke's; as mentioned earlier, I have seen it claimed as a Civil Rights anthem but haven't found much direct evidence. Perhaps it's both the strength and the weakness of the song that it can be appropriated for so many purposes, from jeans upwards (A Change ... could only be used to sell night sticks). Nevertheless, Ben E King's childhood in the South cannot help but be part of the song, and even though it's directed towards a lover its plea for support, for some sign of common humanity, seems bound up with the time in which it was written.

And I don't think he's being false to his gospel roots by taking its poetry to a wider audience, as Cooke was accused of doing. He is, essentially, doing what he said he did as a teenager: taking a song - or in this case a whole tradition - and making it his own: a personal statement that has proven itself over the years to be universal, as illustrated by this remarkable Playing for Change video of street singers around the world united by the song:

I didn't realise quite how personal the origin of King's statement until looking over the net just now. I knew that the rage which Cooke is sitting on in A Change ... stemmed in part from an incident when Cooke and others were arrested in Shreveport, Louisiana, for "disturbing the peace" by trying to register at a white motel but had no idea that for all the sense of apocalypse in Stand By Me its composition seems to have owed something to an entirely happy circumstance:

I was also newly married and I thought that enhanced the song. I had a feeling of love in my heart and romance in my soul.And King's own, rather more succinct, take on the song?

Straight out of church. And a few parts Harlem. Sweetened up with some plush Broadway strings.Gerri Hershey's book tells us that the newly married Kings (or Nelsons) moved to New Jersey to start a family and keep his children free from the streets where he was brought up.

He still goes back to those streets. "My training ground," as he calls them. But he always goes alone. driving in over the George Washington Bridge, down the West Side to 116th and Eighth Avenue, where the Sultans whopped and the Five Crowns doowopped. And where now, the dominant rhythm is the junkie's nod.I had thought of ending this piece with a youtube clip of a karaoke Stand By Me, and say over to you, dot dot dot. But it seems more fitting to give Ben E King back his voice - in two senses.

"I park my car and I walk. I see myself there if I don't be cool. And I've seen myself there quite a few times if I didn't be cool to the point where I could say, 'Hey, nothing spectacular about you, babe. You just have a voice. Just that one thing."

I have written in this and other entries of his diminished vocal power. I even wondered, near the start of this piece, whether my reaction to his performance in Glasgow may have been a sentimental one, that what I took in at the time as a more truthful performance than his louder cabaret buddies could simply have been an underpowered one.

Two performances, twenty years apart, put the lie to that. The first shows King, high on his revival in 1987, at the Montreux Jazz Festival, in an extended workout of his song. He thanks us for giving him a hit record when we should be thanking him. At the end he makes a gesture: "I can't do any more," which seems to apply both to his voice and himself. It's more than enough.

There, finally, we leave The Song. This last video finds Benny near his training ground in a tribute to the late Doc Pomus at Prospect Park, Brooklyn, on the 22nd of July 2007. Almost fifty years on from when he first recorded it as a member of the Drifters, he sings a beautiful and touching reworking of Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman's This Magic Moment, lingering over phrases, feeling the words afresh - doing, in short, everything which I had stopped trusting myself to believe he had done in Glasgow on whatever date it was in a genteel theatre in the mid-eighties.

So no: not Archie Rice, never Archie Rice. And as he finally sashays into the darkness with the ghost of those long-ago-learnt Atkins moves, I salute him and return his thanks.

[To close, another reposted piece, written not long after the above]

Stand By Him

As a footnote to the post about Stand By Me, two youtube clips with a bearing on my comments about seeing Ben E King with the Drifters in the eighties. These appear to be two segments from the same 1986 British TV programme, although that may refer to the date of transmission, as Unca Marvy says King only toured with the UK Drifters between 1982 and 1985.

They may be taped on location at a Manchester cabaret gig or more likely in a studio mock-up: the audience are seated at tables with little red shaded lamps. They are backed by a reasonably sized band who may have been their regular touring musicians at the time. I can't see clearly in the clip but I think I recognise the MD from the Glasgow gig, a middle-aged man whose bouncy enthusiasm the night I saw them found no answering joy in the facial expressions of at least one saxophonist.

The first clip features Johnny Moore on lead, Ben E King effectively just another Drifter, doing all the movements and harmonies.

Given what I've read about him, he may have been happy just to be making a living but it's still mildly distressing to watch; you want to reassure him: "on the horizon..." but he'd probably assume that was just a request from a Leiber and Stoller nut.

It may well be that this is how the audience likes it, but I have to say that Moore really performs his songs at a rate of knots, which tends to confirm the impression I have retained of him. Yet perhaps it's understandable: he makes the mistake of pausing during the intro to Kissing in the Back Row of the Movies, a big UK hit in the seventies ... then is forced to solicit the applause which doesn't immediately come.

There are some bitter comments about Faye Treadwell accompanying the youtube clip, alleging that she allowed Johnny Moore, the voice of so many Drifters hits, to die penniless. I certainly remember my incredulity when told by a cab driver who had been an occasional keyboard player for the live act that Moore had a house in Streatham, which didn't seem very rock'n'roll.

Go to this page on Peter Burns's website soulmusichq and scroll down to "drifters - the name game" for what seems to be the fullest account available of a sad tale. Burns has written an as yet unpublished history of the group and collaborated with Ben E King on a book which I hope will come out soon. There is also resentment on youtube that after Moore's death a UK version of the Drifters which had the blessing of Moore's family and worked hard to rebuild a fanbase was later forbidden from using the name; some have written of their disappointment when seeing the later Treadwell-approved group. You can find the official Drifters' site, fiercely defending its corner, run by daughter Tina Treadwell, here.

The second clip (below) puts King centrestage; with the others backing him, he sings Amor (good choice for a cabaret gig; the others have maracas etc), Spanish Harlem (with some nice brass) and Stand By Me. What's interesting to see is that the Drifters are properly incorporated into what is really King's solo spot: instead of backing vocals being a fairly small part of the studio recording of Stand By Me, Johnny Moore and the others repeat the title in classic Drifters fashion, suggesting how the song might have sounded had George Treadwell not rejected it for the Drifters at the time.

That thought gives a new perspective on the idea of King being imprisoned, as it were, in the eighties in the UK Drifters. And looking at the net just now, an entry by Gethsemane (good gospel name) on the everything2 site from 2000, here, suggests George Treadwell's rejection of the song for the group was no small thing for Benny:

King recalls the end of the session: "Jerry and Mike asked me if I had anything else I wanted to do. I went to the piano and played a little of 'Stand By Me,' which I'd gone over before with Jerry. So right at the end of the session, we cut it... I had tears in my eyes when I sang it."The source for the information isn't given, but interesting that King does seem to be saying here that Jerry Leiber was already familiar with the song, presumably meaning before the session, therefore allowing time for Leiber and Stoller to have an arrangement ready, as they said at the NFT.

According to Lieber, King came into the session with "four or six bars of lyrics." The scratch percussion was made by the wiry underside of an upside-down snare drum. The bass line was added by Stoller, who arrived halfway through the session. King later claimed that the sadness in his voice came from not being able to perform the song with the Drifters.

But then Leiber is quoted as saying what King brought to the session was very sketchy indeed - which doesn't quite accord with King saying that he worked for two days on the song before showing it to anyone.

This is a discussion which could run and run so I will only suggest that the actual quantity of lyrics brought in is almost irrelevant if those lyrics include the key components which then suggest the rest of the song. Elvis Costello talks of Paul McCartney licking his That Day Is Done (a great gospel-style song, incidentally) into shape; Macca said not to be afraid of repeating phrases, hammering them home - You mean like Let It Be? as Elvis laughingly asked this giant of twentieth century popular music (which is maybe why they didn't collaborate again).

Okay, this is a diversion, albeit sort of related as it's a kind of pop-gospel thing too, so I'm going to go with it. McCartney recorded That Day Is Done on his Flowers in the Dirt album (whose title is a line from the song) but Costello later rerecorded it as a guest of veteran gospel group the Fairfield Four, and in the notes for the group's album I Couldn't Hear Nobody Pray, he talks of how they finished a version in the studio and it was good (I was going to add a "lo" there), but when a TV crew came into the studio, expecting to film the group and Elvis lipsynching to the recording, they decided to sing it live instead and, lifted by the presence of others, that rendition intended for TV had the indefinable magic and so replaced the earlier take on the final album. Costello says it was nearer either to what he intended or the original demo - meaning, I suspect, that while McCartney's version, which mimics the sound of a New Orleans funeral marching band, is a good idea in principle, it just sounds a teeny bit leaden by comparison.

The Costello / Fairfield Four recording is also dear to my heart because it was introduced to me by my Costello-loving friend, late of North Berwick and everywhere else, who correctly assumed I'd like it a great deal. When Elvis began singing - not so much. But when those wonderful grainy harmonies filled the little computer speakers - oh yesss. And having the guy who played piano on pop gospel classic Bridge Over Troubled Water probably didn't hurt either. The title of Paul Simon's song was adapted, as many reading this will know, from Claude Jeter's ad lib in the Swan Silvertones' recording of Mary, Don't you Weep: "I'll be your bridge over deep water if you'll trust in My name." You could even say that the Swan Silvertones' recording constitutes a kind of pop gospel, as it's a very compact version of what might have taken ten minutes or more to build to in live performance.

Gospel in feel as the Costello-McCartney (or was it McCartney-Costello?) may be, however, you could argue that the actual story of That Day Is Done owes more to English folk song: a dead father laments not being able to attend his daughter's wedding, as far as I can work it out.

As you can hear, the group are supporting Costello's vocal on that TV appearance from the start; on the album track they only come in on the first That Day Is Done. There is a touching moment on the album version which can't really be replicated: Costello, half-hesitating, is instantly bolstered up by those other voices, as also happened, I believe, when he sang it at the Festival Hall. I've got a feeling that Frank Skinner, a big fan of the other Elvis, once had the chance to sing a song with the Jordanaires for a documentary or something, and said that their backing helped him, however, temporarily, to be a good singer - or believe he was, anyway.

Which, if it's necessary to tie things up with a nice red ribbon, takes us back to Ben E King, cabaret or not, being surrounded by a group again - and whatever the vintage of the other two singers, Moore went all the way back to Drifters Mk 1, being Clyde McPhatter's second replacement as lead. So maybe, instead of pitying the spectacle of a solo star being forced to muck in with all the fancy footwork when Moore is singing lead, we should feel glad for this second chance, however it came about, for Benny simply to be part of the whole, not forced to carry everything himself.

I was going to end by sniffily adding: "Then again ... not exactly 116th and Eighth, is it?" But watching the King/Drifters segment again to try to grab an image for the top of this entry I was reminded of a barely audible "Yeah!" from another group member when Benny launches into Stand By Me. If that was Johnny Moore, then maybe that's all that needs to be said. "You never felt alone, is all."